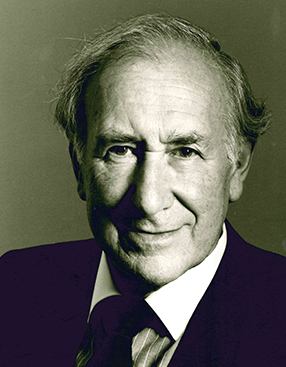

Eric Brenman (1920-2012) was an astute and compassionate clinician, who stressed the need to acknowledge the reciprocity of the analytical relationship, so that both analyst and patient can recognise the value they have for one another.

Eric Brenman (1920-2012) was an astute and compassionate clinician, who stressed the need to acknowledge the reciprocity of the analytical relationship, so that both analyst and patient can recognise the value they have for one another.

He explored the internal and external forces that can interfere, both in the analyst and in the patient, with a stable internalisation of a good object. The recovery of the good object relationship, which follows the working through of the depressive position, is the central task of every analysis. All his major papers appear in a book, Recovery of the Lost Good Object (Routledge 2006).

Life and career

Brenman was born in London to a Jewish family who came originally from Odessa. He grew up in north London and trained at St Bartholomew’s Hospital Medical School. After qualifying as a doctor, he joined the army and was on the ships that took part in the D-Day landings. After the war he worked as a psychiatrist first at the Hammersmith Hospital and then at Napsbury Hospital. From 1950 to 1955 he was a senior registrar at the Tavistock Clinic, when Jock Sutherland was the director. He qualified as a psychoanalyst quite young, at the age of 34, in 1954, and from 1955 he worked full time as a psychoanalyst in private practice. He remained very connected to his identity as a doctor. He was analysed by Hanna Segal. He was married to Irma Brenman Pick, another prominent Kleinian analyst – he and Irma travelled and taught extensively throughout Europe. He was a training and supervising analyst of the British Psychoanalytical Society. He also served as President of the British Psychoanalytical Society and as Vice-president of the International Psychoanalytical Association.

He was instrumental in promoting clinical dialogue between people of different theoretical persuasion at a time when the differences within the so-called three ‘groups’ in the British Psychoanalytical Society were generating tension and conflict.

A cultured man who favoured a humanistic type of psychoanalysis, Brenman’s papers often contain references to the wider world of art, literature and philosophy, promoting cross fertilisation with other disciplines.

His wisdom, his sense of humour and his compassion were much appreciated by those who worked with him.

Early object relations

Brenman attributes a central role to the mother's capacity to help the infant give up the primitive system of defences (omnipotence, splitting, projection of the death instinct, insulation) originally deemed to be essential for survival. The seductive ‘falsehood’ of omnipotent defences can be gradually given up in favour of the truth of the human relationship that develops between the mother and her infant.

Brenman is very interested in how this unfolds in the transference. If the analyst has to help the patient face what is believed to be unbearable, the patient needs to have the experience of an analytical object who can be truly capable of facing what is unbearable, and can face his own feelings of hopelessness and worthlessness, especially when the patient questions him as a truly good object. The patient observes the analyst in his entirety and great attention has to be paid to how the analyst is internalised. Brenman warns against the analyst presenting himself as a perfect, all knowing narcissistic container: this would only promote further narcissistic identification, confirming the patient's hopelessness about achieving true and limited human understanding. The analyst, like a good mother, should be mindful both of the hold of primitive defences and of the value of human understanding, enabling the patient to face the vicissitudes of life. Analysis provides the patient with the opportunity of a different exploration of his or her own history.

The primitive superego

Brenman believes that the superego, in particular the primitive ruthless superego (the prototype of which is the melancholic superego described by Freud and Abraham) shapes the conflict between love and destructiveness and determines its outcome. Loving human understanding can moderate its severity. Such superego takes hold when the internalisation of a good object has failed. The superego, which attacks the very value of human understanding, is like a fundamentalist god that demands total devotion. Brenman makes an important theoretical and technical point: interpretations about destructiveness can only be meaningful if the patient has some access to some good object relation. In severely depressed and narcissistic patients, or patients stuck in a sado-masochistic impasse, an interpretation about destructiveness can be heard as a reproach from another inflexible superego, which demands that the patient should be ideal and free of hatred.

Gigliola Fornari Spoto 2014 – courtesy of the Melanie Klein Trust

Click here to read Brenman's publications on PEP Web

Video: Encounters through Generations: a conversation with Eric Brenman

Key publications

2006 Brenman, E. Recovery of the Lost Good Object. (ed G Fornari Spoto) Routledge.