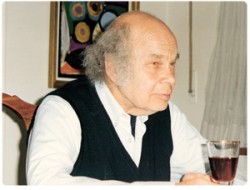

Donald Meltzer’s many original contributions to psychoanalysis grew particularly from his capacities for very detailed clinical observation, his involvement in child analysis and his interest in aesthetics and philosophy.

Donald Meltzer’s many original contributions to psychoanalysis grew particularly from his capacities for very detailed clinical observation, his involvement in child analysis and his interest in aesthetics and philosophy.

Most widely used are his theories of an intrusive form of projective identification, of autistic two-dimensionality and of what he termed the ‘aesthetic conflict’ at the start of life.

Training, career and influences

Meltzer (1922-2004) was born in New Jersey, USA, and studied medicine at Yale University and later at Albert Einstein College in New York. He completed his psychiatric training in St Louis, Missouri, and decided to enter child psychiatry and pursue his interest in Melanie Klein’s ideas. In 1954 he was able to get a posting to London from within the US Air Force for whom he worked as a child psychiatrist. He began an analysis with Klein and soon after this left military service and was accepted for training in the British Psychoanalytical Society.

His adult cases were supervised by Hanna Segal and Herbert Rosenfeld, and he went on to train as a child analyst, a combination more frequently undertaken at that time by talented young analysts than it now is. His child cases were supervised by Betty Joseph, Esther Bick and Hanna Segal. Subsequently he was much influenced by friendships with Roger Money-Kyrle and Wilfred Bion.

Nourished by the richness of analytic thinking in the British Society in the 1950s and 60s, he became a training analyst and a sought-after supervisor, and also developed close links to the child psychotherapists being trained at the Tavistock Clinic in the training started by Esther Bick at John Bowlby’s invitation. Also significant to him was his membership of the Imago group, which brought together distinguished art historians, philosophers and psychoanalysts and which deepened his interest in aesthetic experience.

His psychoanalytic writings are extensive and led to a worldwide interest in his ideas. This provided him with many opportunities to travel and teach abroad. After the breakdown of his relationship to the British Society in the early 1980s as a consequence of disagreement about the Society’s organisation and rather bitter personal animosities, he continued to live and practice in Oxford. His ideas as a teacher were particularly appreciated in South America as well as widely in Europe. He also maintained his links to child psychotherapists through his third wife, Martha Harris, who ran child psychotherapy training at the Tavistock.

Describing the analytic relationship

His first book, The Psychoanalytical Process (1967), signalled his special interest in clinical description of the evolution and vicissitudes of the analytic relationship. It is uncompromising in its focus on the patient’s inner world and on the primacy of psychic reality. Among his subsequent books, Explorations in Autism (1975) and The Claustrum (1992) explore specific clinical phenomena in great detail. The autism book was the first of a number which he published jointly with others, and his role as a theorist working with clinical colleagues is a notable feature of his preferred way of developing his ideas, as his ‘atelier’ (workshop) model of psychoanalytic thinking had perhaps suggested. Later The Apprehension of Beauty: The role of aesthetic conflict in development, art and violence (1988), written jointly with the literary scholar and artist Meg Harris Williams, demonstrates a similar collaboration.

His most influential ideas include some which are widely recognised and others much debated. His strikingly original early paper ‘The relation of anal masturbation to projective identification’ (1965) set out a view of an intrusive form of projective identification which was related to a failure of genuine development and consequent identity confusion. These ideas were more fully revisited in The Claustrum, which elaborated his understanding of the functioning of anti-developmental forces in the mind, sometimes functioning in gang-like mode, and the sealed-off quality of a personality based on this avoidance of awareness of dependence on the object. This theory has obvious links to Rosenfeld’s view of anti-libidinal narcissistic object relations and to Steiner’s ‘psychic retreats’. Among clinicians working with autistic children, the description of the dismantling of ‘common sense’ (Bion), the two-dimensional quality of relating, the sticking to surfaces (adhesive identification) and the pervasive mindlessness have proved particularly valuable.

Aesthetic conflict

In his later work, Meltzer became more interested in the contribution of infant observation to the understanding of early mental development and also to the function of the family. The paper written for UNESCO, ‘A psychoanalytical model of the child-in-the-family-in-the-community’ (Meltzer and Harris, 1976), is unusual in its attention to the impact of the qualities of the parental couple, the mode of containment and the meaning of the wider social context for children’s potential development.

The years of joint travel and teaching with Martha Harris were also the backcloth to his formulation of a revised picture of early infancy, in which the ‘aesthetic conflict’, that is the impact on the baby of encountering the ‘beauty and mystery’ of mother, was placed at the beginning of life, and the Kleinian account of paranoid-schizoid phenomena seen as a defensive retreat from this. Perhaps the contemporary view would be that the subtle variations in the forms of mother-baby relationships are so numerous that these ideas are not alternatives but likely to be of differential centrality and to come to the fore at different times in the individual case.

Psychoanalysis as an art

Meltzer’s emphasis on the aesthetic dimension of life and of psychoanalytic work and understanding is, however, a unifying strand in his writing. It is already evident in his first book that notwithstanding his medical training and taste for theory, his heart lies with the conception of psychoanalysis as an art. His dislike for the messy complexity of institutions and politics might be seen as another dimension of this attitude. For him, individual creativity always mattered most. His books, which pay rather little explicit attention to other psychoanalytic writers (with the exception of The Kleinian Development (1978)), have their life within the atmosphere of the consulting room and in the broad landscape of the psychoanalytic ideas he valued. The reader is likely to be impressed, even overwhelmed, certainly challenged by his clinical imagination and grasp of mental process, but also at times frustrated by the idiosyncrasy of his forms of thought and writing.

Margaret Rustin 2013 – courtesy of the Melanie Klein Trust

Key publications

1967 Meltzer, D. The Psychoanalytical Process. Heinemann.

1965 ‘The relation of anal masturbation to projective identification’, International Journal of Psychoanalysis. 47:335-342.

1975 Meltzer, D. Explorations in Autism. Clunie Press.

1976 Harris, M. and Meltzer, D. ‘A psychoanalytical model of the child-in-the-family-in-the-community’, first published by United Nations Organisation of Economic and Cultural Development. First published in English in Hahn, A. (ed.) Sincerity: Collected papers of Donald Meltzer. Karnak, 1994.

1978 Meltzer, D. The Kleinian Development. Clunie Press.

1988 Harris Williams, M. and Meltzer, D. The Apprehension of Beauty: the role of aesthetic conflict in development, art and violence. Clunie Press.

1992 Meltzer, D. The Claustrum. Clunie Press.

Other resources

Listen to Donald Meltzer talk about one of Klein’s most famous and complex concepts: projective identification. Meltzer explored her idea through his own formulation of the ‘claustrum,’ a psychical state that he describes in this presentation given in 1990. It was part of the former annual public lectures at the Centre for Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy.